"I don’t want to write about myself. That’s boring..."

I was approached to write an article highlighting the work of a composer, and the tendency in these situations, I think, is to address something that reflects one’s own practice. I could trawl through the British Music Collection and find a composer who thinks the way I do, composes the way I do... but I suppose I would be, in essence, writing an article about myself. I don’t want to write about myself. That’s boring. So, I’ve decided to write about three very unboring composers who do things I don’t/ won’t/can’t do.

Piers Tattersall has written a number of pieces for instrument and analogue radio; my favourite of these is I work carefully to open my heart (which was composed for the pianist Christopher Guild, and also features electronics). The consequence of having both an analogue radio and fixed electronics part is that Piers retains an incredible level of control over the duration of the piece, but relinquishes control in other areas. This was particularly apparent when I heard a wonderful performance of it in Sheffield last year. Piers uses the radio in three ways: tuned to white noise (utilised in a remarkably percussive way in his previous work Contrapunctus Republic), tuned to a station with lots of talking, and tuned to a station with lots of music. At the Sheffield concert (midway through the piece, and for a relatively long period of time) the radio was tuned to a station broadcasting an opera. Normally, as a composer, you have some control over what the audience focuses on, I think, but by allowing a situation to exist where the radio ‘played’ something musically interesting, I felt like Piers was tacitly inviting me to disengage with his musical material and engage with the music of this other anonymous, dead composer. In doing so, I realised that whilst the unpredictable nature of tuning into a radio station makes each performance of I work carefully to open my heart unique, the broadcast of the opera was also changed by Piers’ intervention. My experience of that opera – and I will never know what opera it was – is permanently tinged with piano and electronics, and is much better as a result. (My ambition is to have a piece of mine broadcast on radio, and for that broadcast to feature in a performance of one of Piers’ radio pieces, and for neither of us to ever know about it...)

Jenny Jackson’s Sanctum is another work for piano; this time without radio and electronics... and also without piano. Jenny describes how she was ‘transfixed watching how carefully and beautifully Philip [Thomas] performs extremely quiet music such as Feldman’s piano pieces’, and has composed a piece (for Philip) where he is asked to play so softly, he does not play at all (instead, ‘his’ notes are performed by off-stage musicians). Composers are expected to have portfolio careers; CVs full of works performed by famous soloists and ensembles, with high quality recordings as proof. To convince somebody as brilliant as Philip to play your music, and then have him play no audible notes whatsoever completely flies in the face of this idea of the ‘portfolio composer’. I love it. It’s almost iconoclastic. But the thing is, it also really works as a piece of music, especially live. It’s captivating, and – perhaps unintentionally – very tense indeed.

Paul McGuire has written a percussion quartet for four instruments, two of which aren’t percussion instruments... or maybe they are. Is a percussion instrument an instrument that is designed to be struck, or is a percussion instrument an instrument that IS struck? In any case, this piece is written for two prepared floor toms and two prepared acoustic guitars, and nothing happens and something definitely happens, and the loudest moment of the piece is silent or, perhaps, it’s the moment after the silence. Changes in timbre are sudden and small; but, given that timbre is the only thing that really varies, these moments feel massive. Or, actually, it feels like this is a recording of a really small, fast machine, amplified and slowed down, and made to feel massive. I played it to my undergraduate composition students, and one of them remarked ‘you know when you say the same word over and over again, and it loses all meaning? This piece is like that.’ If I were Paul, I’d take that as a huge compliment.

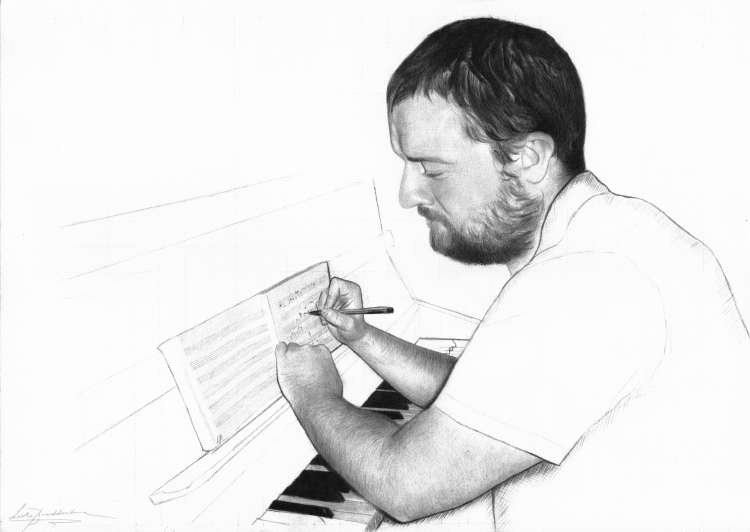

[[{"fid":"9057","view_mode":"default","type":"media","link_text":null,"field_deltas":{},"attributes":{"height":220,"width":220,"style":"width: 220px; height: 220px;","class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{}}]]

I hope you’re not expecting a final paragraph that wraps things up neatly, and finds some common ground between these composers and their pieces. Sorry.

Ben Gaunt