"Graphic scores have the potential to challenge some of the traditional creative hierarchies by perpetuating more democratic, inclusive forms of music making and appreciation." #BMC50

[[{"fid":"13784","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":413,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"1"}}]]

[Caption: Fresh Yorkshire Aires at The Gallery at Munro House, Leeds/ Photograph (c) 2016 by Matthew Moorhouse/ Pictured work: Sound Sculptures photographs by Liz Osborne (left) and selections from Angelystor by Phil Legard, with photography by Layla Legard (right).]

INTRODUCTION

Graphic scores offer opportunities for experimentation and multi-media forms of composition, participatory practice, site-specific work and creative ways of listening to the world around us.

They form a large part of my own compositional practice and I have been fortunate to meet many other composers and artists making fascinating work that uses visuals to convey sonic or musical experiences.

Exploring the work of my contemporaries has shown me that notation can encompass everything from graphic symbols to text, photography, illustration, video and sculpture.

This exhibition is divided into four parts: Storytelling, Composing as Performance, Place and Landscape, and Listening. Each section explores different approaches, to celebrate just some of the ways in which British artists are working with graphic scores today.

The artists featured use graphic scores to tell stories, to map or document the sounds of a specific geographical location, to encourage people to listen again to their surroundings, and to examine issues of authorship and compositional process.

PART 1: STORYTELLING

Graphic scores can offer evocative forms of storytelling, bringing together the sonic, visual and emotional aspects of an event or place. The score is a storybook that can be seen and heard, recounting a narrative that has already happened, whilst providing an impetus for people to make and imagine new sounds.

Angelystor

Phil Legard

[[{"fid":"13785","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"2":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":460,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"2"}}]]

[Caption: Angelystor by Phil Legard, pages 3 (top left), 9 (top right), 10 (bottom left), 13 (bottom right)]

Phil Legard’s score is inspired by the folk heritage of the churchyard of St Digain, in the Welsh village of Llangernyw, home to the oldest living thing in the British Isles - a 5,000 year old yew tree.

Through graphic notation, illustration and visual collage, Legard’s score retells the story of ‘Angelystor’, the angel of death. Each year, the spirit is said to visit the church on All-Hallows’ Eve, announcing the names of those who will die in the parish over the coming year.

Folklore tells of a local man, John Ap Robert, who challenged the truth of this story. One Halloween night, he goes to the churchyard to disprove the legend. But, as John Ap Robert is standing in the churchyard at midnight, Angelystor appears and the disbeliever hears his own name called out prophesying that he will die the following year.

Anyone can take Legard’s illustrated pages and use them as the basis for a musical improvisation. At the same time, Angelystor records something of the feel and heritage of the location on which it is based. Legard’s score is also partnered with an extended sound work weaving together music and field recordings from the location, with the score acting as a kind of map for listeners.

Angelystor trailer:

[[{"fid":"13795","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"8":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":360,"width":480,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"8"}}]]

Three Box Scores

Adam de la Cour

[[{"fid":"13786","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"3":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":827,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"3"}}]]

[Caption: Box 1: The Amputee, by Adam de la Cour. For quarter-tone tuned e.guitar/2 hairdryers/VCR hum/breathing/laughter]

These box scores by Adam de la Cour tell a story in a more abstract way than Legard’s score but they are nevertheless each inscribed with narrative meaning.

Box 2: The Foetus on the Sofa

Adam de la Cour

[[{"fid":"13787","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"4":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":833,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"4"}}]]

This box score traces a surreal kind of autobiographical narrative, made possible only by the physical and literary media through which it is conveyed.

The box blurs memories of childhood, with recollections of film and artworks de la Cour has seen, featuring transcribed choreography from Jacques Tati's Playtime, and elements from Duchamp’s With Hidden Noise. The box is even etched with the murmurings of a daemon voice, recalling childhood nightmares.

The instructions tell us the score is to be realised by “2 vacuum cleaners/vocalist in foetal position on a sofa/'daemon' voice/sample of a cat purr”.

The inevitable distance between the musical interpretation and the physical features of the box itself is perhaps analogous to the fuzzy recollection of nightmares and past cinematic encounters that inspired this work. Listen on SoundCloud

Box 3: The Mirror Dwarf

Adam de la Cour

[[{"fid":"13788","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"5":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":830,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"5"}}]]

This score offers a similarly cryptic retelling of scenes from Werner Herzog's Even Dwarfs Started Small, tracing the movement of the characters on screen.

The dwarf laughter is also referenced and sampled in the recording. The DVDs found within the box contain footage of the original camera traces, to be imitated (indicated by the mirrors opposite each DVD panel when the box is closed).

At the End of School Assembly

Shiva Feshareki

[[{"fid":"13789","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"6":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":463,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"6"}}]]

[Caption: At the End of School Assembly, page 1 of 4, by Shiva Feshareki]

[[{"fid":"13790","view_mode":"default","type":"media","field_deltas":{"7":{}},"link_text":null,"fields":{},"attributes":{"height":463,"width":620,"class":"media-element file-default","data-delta":"7"}}]]

[Caption: At the End of School Assembly, page 2 of 4, by Shiva Feshareki]

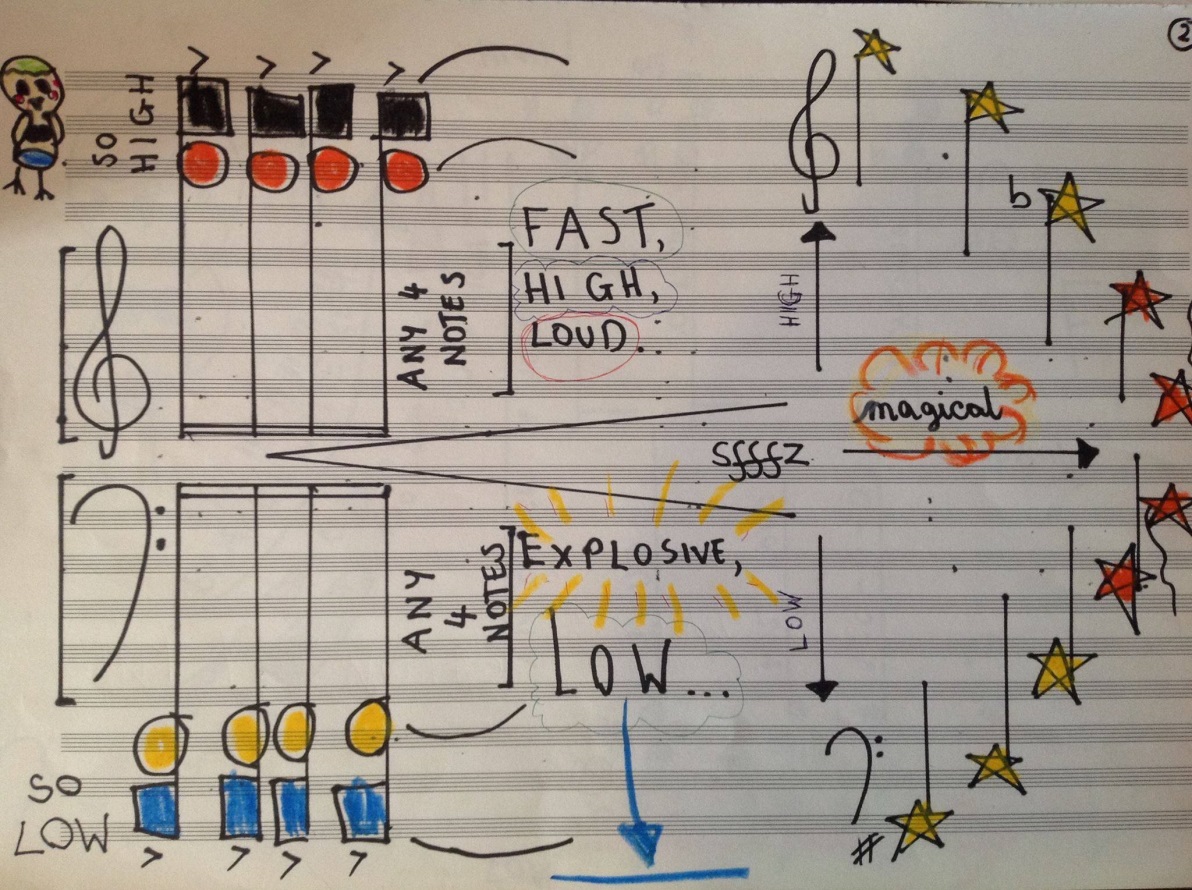

Graphic scores have the potential to challenge some of the traditional creative hierarchies by perpetuating more democratic, inclusive forms of music making and appreciation.

Shiva Feshareki’s score (above) is inspired by stories written to her by nine-year-old school children. In the first performance, at the Royal College of Music in 2014, the children also narrated their stories alongside the composed scores.

This piece is an example of how the combined media inherent within graphic scores can allow composers to communicate on a variety of levels.

The work reveals its origins through the imagery, speaking directly to the young people who provided its narratives, whilst allowing any performing musician the license to bring their own musical experiences to bear on the interpretation.