In the second of a four-part curatorial series, Amble Skuse explores examples of cultural critique through performances art.

In the second of this four-part curatorial series, Amble Skuse explores examples of cultural critique through performances art.

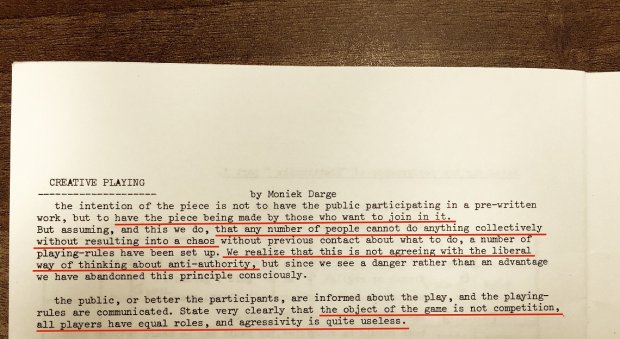

In this piece by Moniek Darge (from The Logos Anthology) she explores ideas around democracy and anarchy. She is looking at the power balance between the composer, ensemble and audience. She rejects the notion of hierarchy (a composer deciding what should be done) and embraces the idea of those involved deciding what should be done. She stops short of total anarchy because “any number of people cannot do anything collectively without resulting into a chaos”. So we can see that there are certain accepted sonic sensibilities influencing that choice. (What is wrong with chaos?).

She then explores a feminist idea, “the object of the game is not a competition … and agressivity is quite useless”. By framing the work as a ‘game’, she understands that there will automatically be assumptions of “winning and losing” amongst some players. She knows that she needs to reframe the idea of a game as something collaborative.

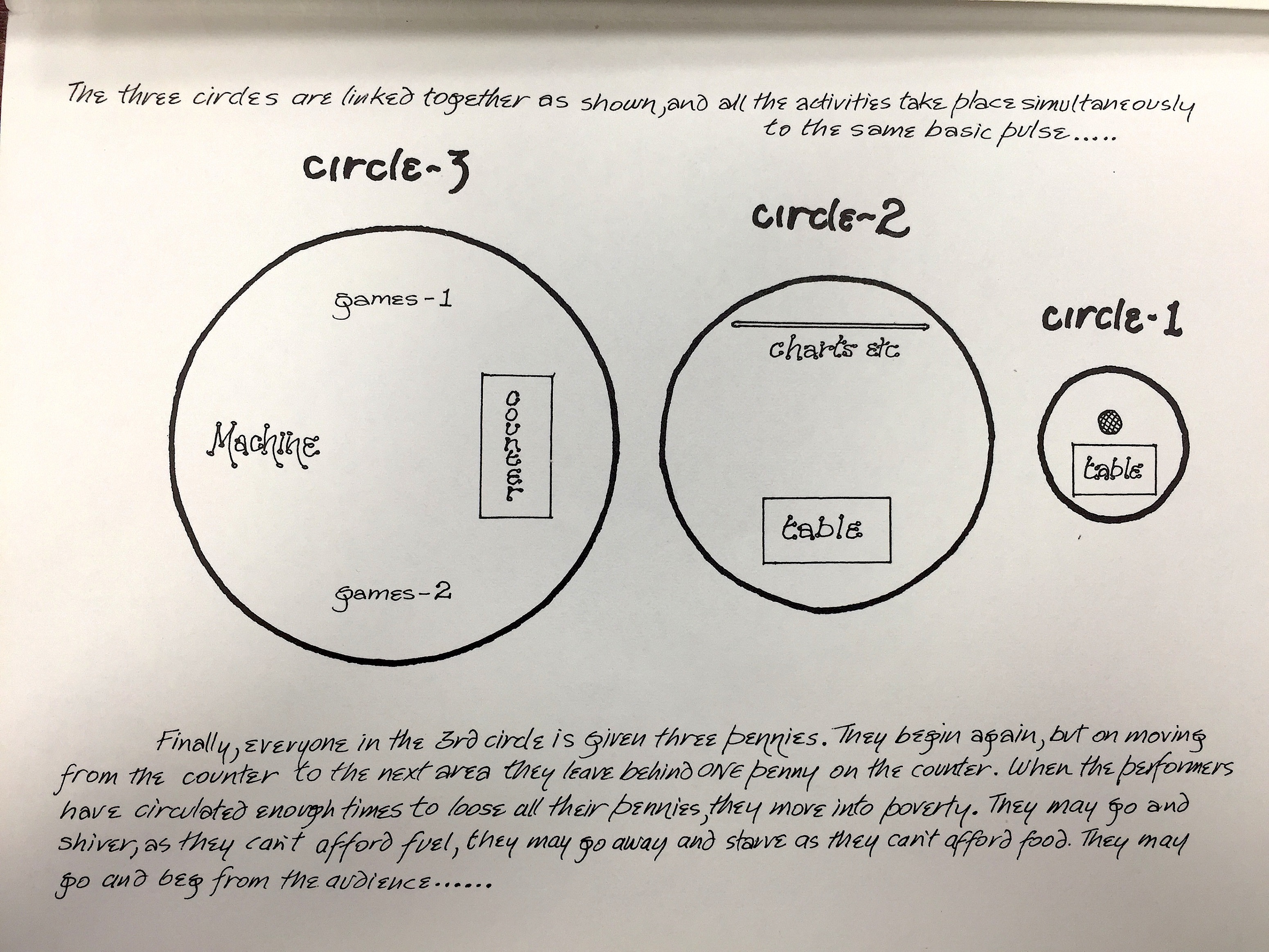

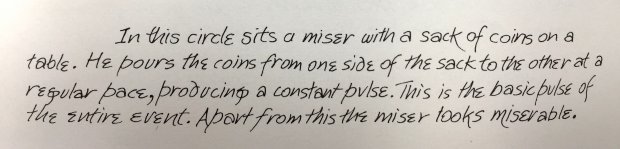

In Trevor Wishart’s “Bread-Show Music” he is working with a group of young people, to make a theatre show, and using experimental performance techniques to create a soundscape and music performance.

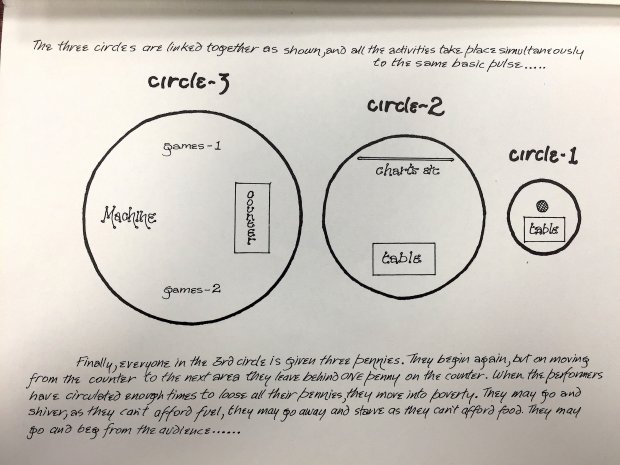

In it, he delivers a fairly cutting review of Capitalism. The miser counts his sack of coins to create a beat, the business men process the cash, four people sit at a machine, producing goods and profit, passing it to the business man, and then the ‘people’ buy the goods, passing the money from the people to the business men to the miser.

“When the performers have circulated enough times to loose all their pennies, they move into poverty. They may go and shiver, as they can’t afford fuel, they may go away and starve as they can’t afford food. They may go and beg from the audience.”

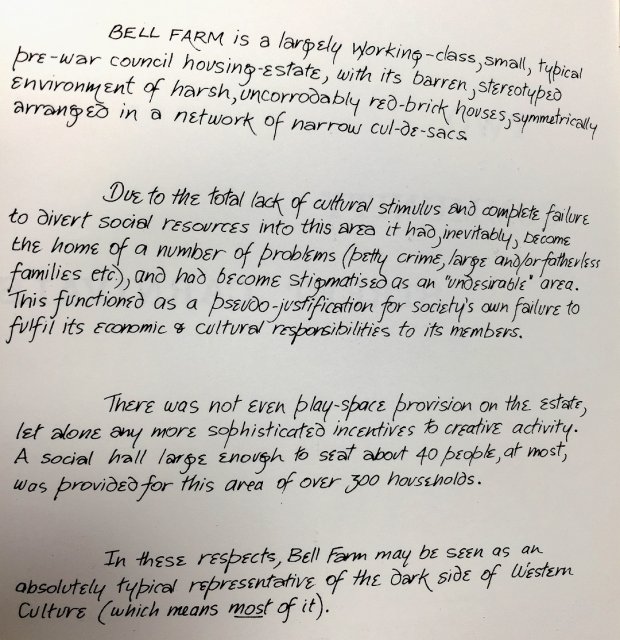

In Wishart’s Bell Farm Carnival he works with the local community to develop ideas for the carnival. He explains the cultural and social situation of the community, an “undesirable” area.

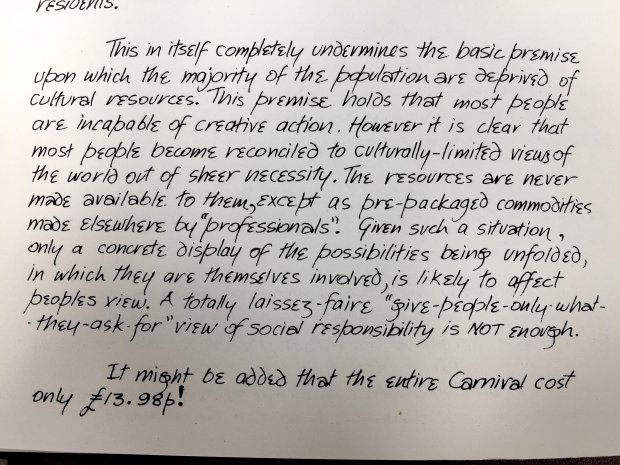

I’m not going to explore the participatory process of Wishart here, which is mainly community led. But rather focus on the attitude of the funders – external agencies which decide what is worth delivering. Tied up in this are ideas are who can be ‘creative’.

Wishart is highlighting differences between the perceived values of Big c culture and little c culture (as described by Herron in 2000). Big c culture are things we think of as artistic pursuits, violin concertos, novels, theatre, opera, etc. Little c culture is what’s around us, how we greet our friends, the formality of our group, chosen foods of a certain group, street fashion trends, etc. It can also spread into a grey area when we talk about “Participatory” or “Community” arts. It’s the gap between what the community want to express and make, and what the professional artists think is good for them.

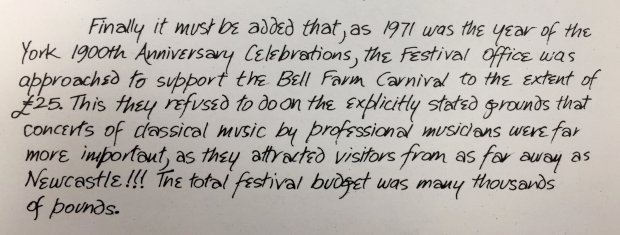

Wishart encounters this when he approaches York Council Festival Office for a small grant. Their response is that the big c culture has more value than what he is proposing (grass roots small c culture).

This dilemma sits at the heart of so much arts funding. What about HipHop, is it art? Graffiti? Is it art? How much should we spend on Opera? How much of our arts funding is directed at the educated middle classes and their ideas of big c culture? How much of the culture of the UK is dismissed by those who value ART over culture? Interesting stuff right?

Amble's series will continue next week